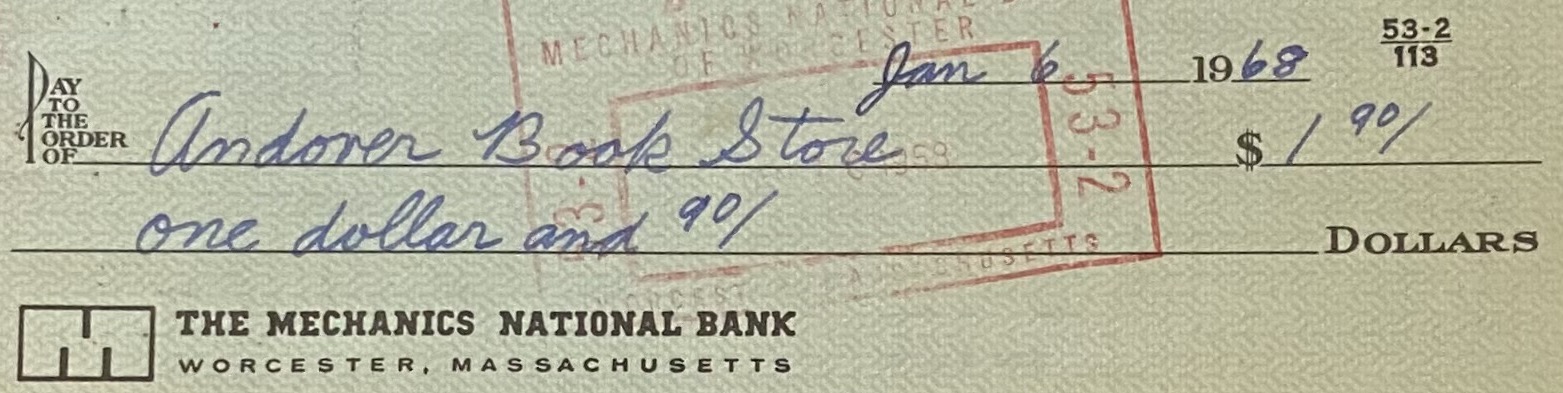

The other day I came across a clutch of canceled checks (remember those?). I found myself wondering (fruitlessly it turns out) what I bought for $1.90 with that first check I ever wrote. The date was January 6, 1968–when Lyndon Johnson sat at the Resolute Desk and the Boston Red Sox sat on the American League throne. I was in tenth grade.

One helpful clue (obviously) is the payee: a book store in Andover, which still exists.

Another helpful bit of information is knowing that $1.90 in 1968 is roughly equivalent to $15.28 in 2021. (That takes us out of the penny-candy aisle.)

What on earth might I have bought for $1.90 at that bookstore in 1968? (I am disregarding the 3 percent sales tax because among the many exemptions–including feed, fertilizer, human food, clothing etc.–were books required for religious worship and formal education. That last phrase likely applied to the store because it supplied textbooks and reading material for nearby schools (including the two boarding schools up the street).

There’s a chance the money went for the 1963 edition of Sound and Sense. We used that collection of poetry that we used in English that year (“Ozymandias” and all that). I can’t find that copy so I don’t know what it cost. I still have a copy from that year of C. Vann Woodward’s The Strange Career of Jim Crow. It cost $1.95. Sound and Sense makes…. sense. However, we used that book all year. I should have bought it in September, not January, right?

I’m kind of intrigued by the thought that the $1.90 covered the cost of two 95-cent paperbacks. I like the math. That sounds sensible enough. There were plenty of such books, some published by Dell, for example. I remember holding in high school, if not reading: James Clavell’s Tai-Pan, Erwin Nathanson’s The Dirty Dozen, Bernard Malamud’s The Fixer, Robert Crichton’s The Secret of Santa Vittoria, and Anatoly Kuznetsov’s Babi Yar. Did I buy one of those on January 6?

I know I never touched, bought, or read Jeanette Kamins’ 95-center, A Husband Isn’t Everything. Some paperbacks were less than 95 cents, of course. Richard Fariña’s Been Down So Long It Looks Like Up to Me cost three quarters.

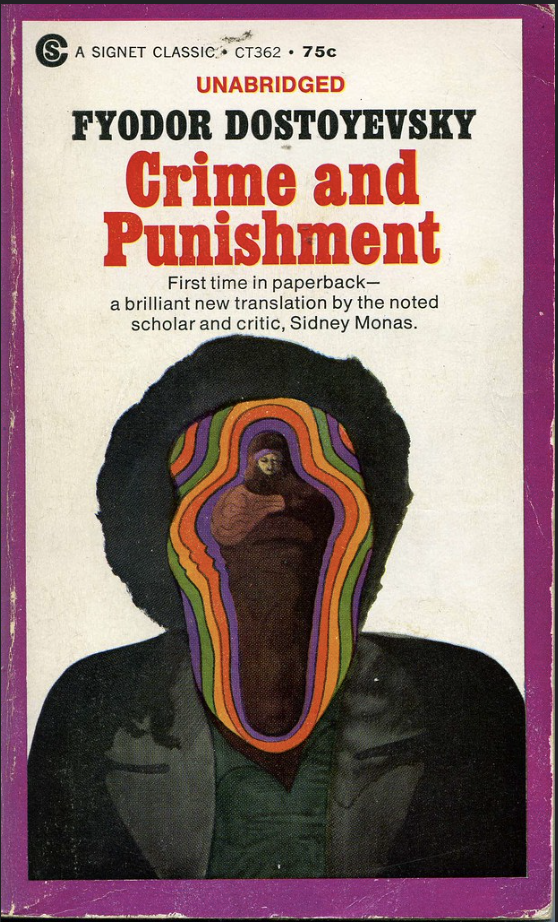

So did Signet’s Crime and Punishment (right). I remember reading that in tenth grade. For some reason that coincided with a decision never to go inside a pawn shop. It came out in early 1968 and cost 75 cents. I definitely remember the cover (right). Was it available in January? Not sure.

Or did I buy Robert Ardrey’s African Genesis–another 95-center from Dell.

Or was it the massive Worlds in Collision by Immanuel Velikovsky, despite its cover price of $1.95? I know I read it that winter. I remember the cast-iron radiator I sat near–looking for warmth, security and protection. The book terrified me. But I could not stop reading it. One source at the time said Velikovsky “propounds the theory that more than once within historical times the earth was subject to enormous cataclysms—deluges of flaming matter, annihilation of large portions of the human race, and destruction of land masses.” Now that’s a pretty good bang for the 1968 buck or two.

But I’ll never know what I bought, no matter how much I ponder, burrow, or Google.

This wasn’t a total waste of time, though.

While looking through paperbacks of the late 1960s, I came across a 1967 survey carried out by the National Council of Teachers of English. According to various newspaper article, the group asked seniors at 116 schools to list the ten most significant books they had read.

Here are the 10, chosen by students, in no particular order:

Lord of the Flies

Catcher in the Rye

1984

To Kill a Mockingbird

Crime and Punishment

Gone with the Wind

The Robe

Black Like Me

Cry the Beloved Country

The Bible.

That’s quite a list. Might serve as a good start for a book-group. I have read seven of them to date, but only five by the time I was a senior in high school.

Many of those still draw praise, and criticism, of course. Catcher in the Rye still rubs people the wrong way. I particularly enjoyed reading about a couple of examples (which MIGHT be true):

First, in the June 1966 edition of the ALA Bulletin (“My Mother, the Censor”), Rozanne Knudson mentions that in the early 1960s one watchdog thought Catcher in the Rye was so horrible that the author had no business being on the staff of the White House under President Kennedy. They, of course, had confused Salingers–J.D. for Pierre.

2. In a master’s thesis from 1968, a graduate student (perhaps falling prey to an apocryphal tale) mentioned that one critic had the name of the author correct but misheard the title. They saw no place in a school reading list for a book with such a raunchy title as Catch Her in the Raw.